Enabot Hacking: Part 2

Enabot Hacking: Part 2 -> Reverse Engineering

Table of Contents

- Enabot Hacking: Part 2 -> Reverse Engineering

- Packet Analysis

- Function Renaming

- Get all strings and turn to function names

- Get already named function

- Packet Reversing

- Controlling the Ebo

- Hosting an EBO Server

- Conclusion

- Tools

Introduction

Last post we covered the teardown and firmware extraction of the enabot. Initially in this post we had hoped to look for vulnerabilities in the device and look for ways to exploit it. Lain3d ended up working on this as much as Etch did and we ended up getting a bit carried away in a different direction instead 😅. In this post we describe how we emulate all the features of the original phone app, from our own client developed in python. We discuss the process of reverse engineering the protocol, and figuring out how to use the data the Enabot sends us. We think it will be much more exciting now for our next post on the vulnerabilities in the device. We hope you enjoy this post, the whole process ended up being a ton of fun and a lot more challenging than we initially expected 🥳.

Debugging the device

This post ended up getting pretty long so we decided to put our debugging setup in a different page.

Packet Analysis

We are hoping that there is a vulnerability in the basic ways this thing communicates with its raw api. Maybe there is a parsing bug or buffer overflow if we send some ridiculous packet. This program is pretty complicated, with many threads that interact with each other via shared buffers or using RDT.

With this in mind, we opened up wireshark and began looking at the stream of packets as we moved the ebo around. We were only seeing UDP packets and they all seemed to be encrypted in some way.

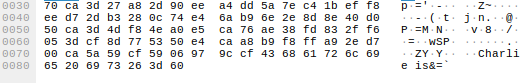

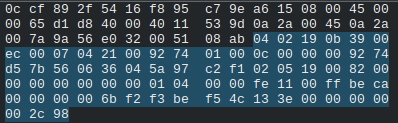

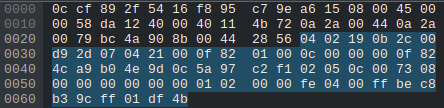

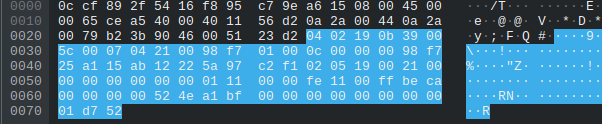

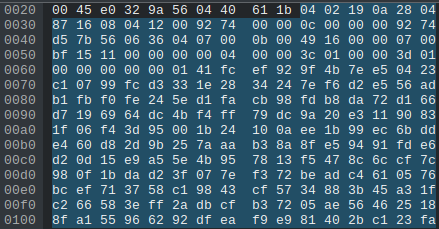

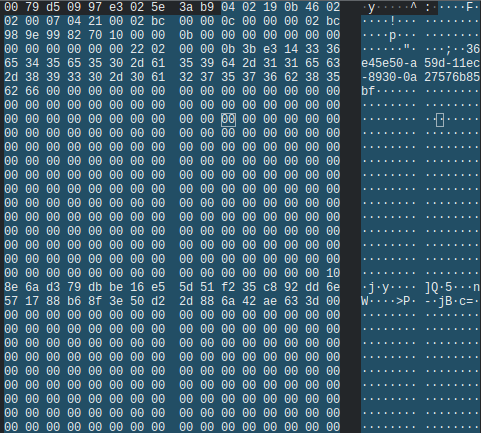

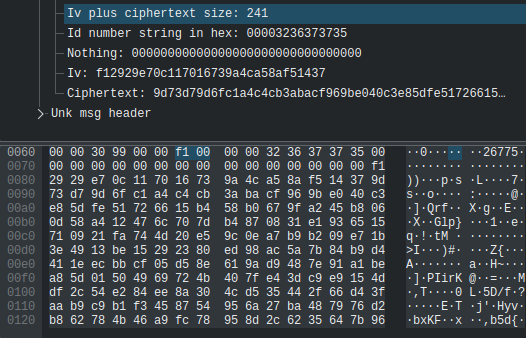

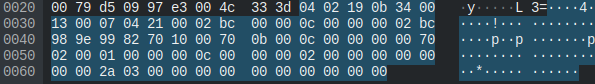

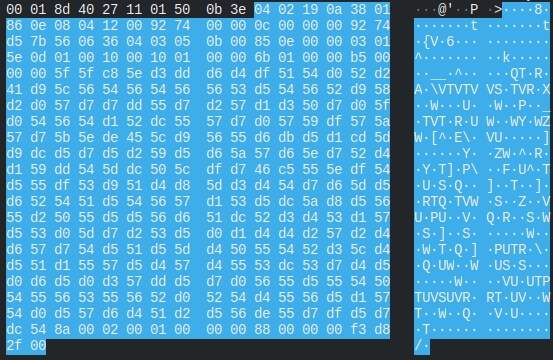

After looking at the data of some of the packets, we noticed this one.

At the end of the packet it say “Charlie is”. There is no way this is some coincidence of randomly generated data. There is probably some XOR encryption going on and those bytes were null bytes. We opened up the firmware in wireshark and checked if there were any strings with “Charlie is”.

There it is. “Charlie is the designer of P2P!!”. We figured whoever made this firmware probably didn’t write that string, so we looked around to see if people had run into it before.

We were able to find these posts:

Hacking Reolink Cameras for Fun and Profit

Privacy Risk IOT CCTV Camera Security

After reading through them it turns out the function is XORing the packet with the charlie string, and then scrambling it, although it doesn’t appear to be scrambled in the packet we just saw. We tried the same thing they mention in the 2nd post where they found the .so file and used the function in it to descramble it, but the packet still just looked like random garbage.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <dlfcn.h>

int main(){

unsigned char input[115] = {

"Packet bytes go here"

};

int output[150] = {0};

char *input_ptr = malloc(sizeof(input));

char *output_ptr = malloc(sizeof(output));

for (int i=0; i<sizeof(input); i++){

*(input_ptr+i) = input[i];

}

int *imglib;

int (*ReverseTransCodePartial)(void *input, void *output, unsigned short length_bytes, unsigned short max_length_bytes);

int imghandle;

imglib = dlopen("./libIOTCAPIs.so", RTLD_LAZY);

printf("Opened imglib: %x\n", *imglib);

if (imglib != NULL) {

*(void **)(&ReverseTransCodePartial) = dlsym(imglib, "ReverseTransCodePartial");

ReverseTransCodePartial(input_ptr, output_ptr, 115, 115);

printf("Ran decoding function\n");

} else {

printf("Didn't work\n");

}

const char filename[] = "decoded.bin";

const char filename2[] = "encoded.bin";

FILE *decoded;

FILE *encoded;

decoded = fopen(filename, "w");

fwrite(&output_ptr, 1, sizeof(output), decoded);

encoded = fopen(filename2, "w");

fwrite(&input_ptr, 1, sizeof(input), encoded);

free(input_ptr);

free(output_ptr);

}

After doing some debugging that can be read about in the separate post, we figured out that this was acurately unscrambling the data. We could see the unscrambled data before it was sent in GDB, and after unscrambling the scrambled packet in wireshark, it matched that initial unscrambled data. This meant the protocol this thing communicated on was just going to be tedious to reverse. We have no strings indicating what each packet does, so we would have to match what the raw bytes in the packet were controlling in the firmware on the device. Also, if we want implement our own client, we will have to unscramble/scramble the data in realtime for receiving/responding to the device.

Function Renaming

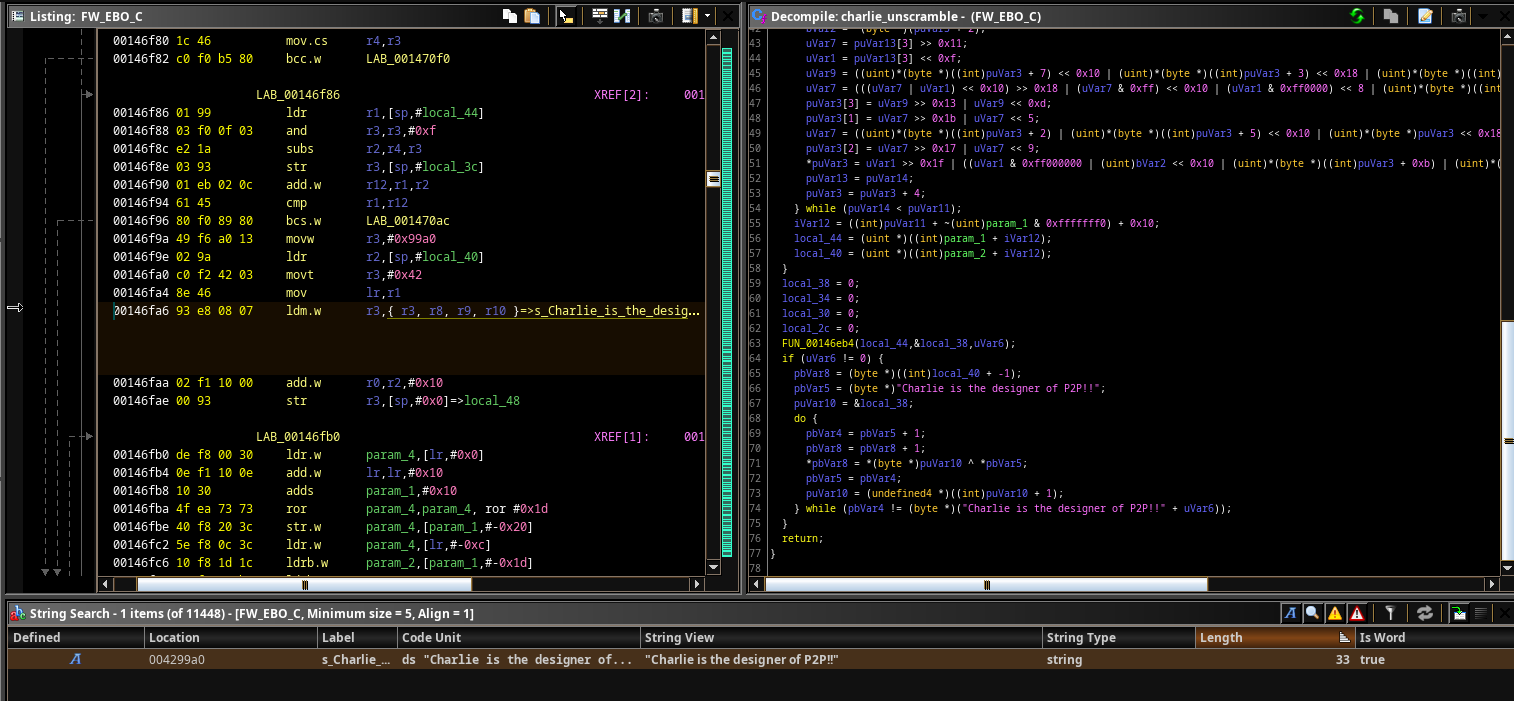

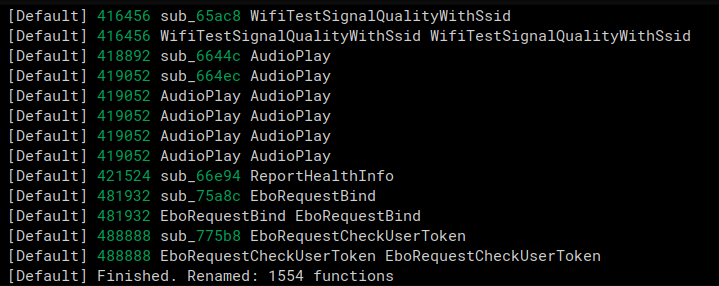

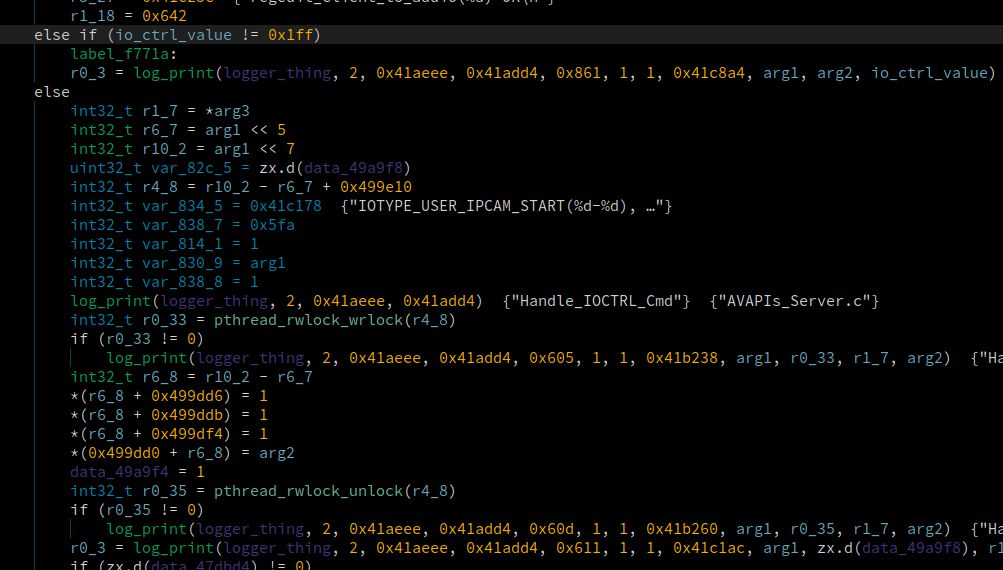

We were able to get a lot of functions renamed from log prints. We had two separate scripts, one that would get the function name based off of a log print of it, and one that would get a function named based off a print after a failed function call.

The first script is for the following scenario

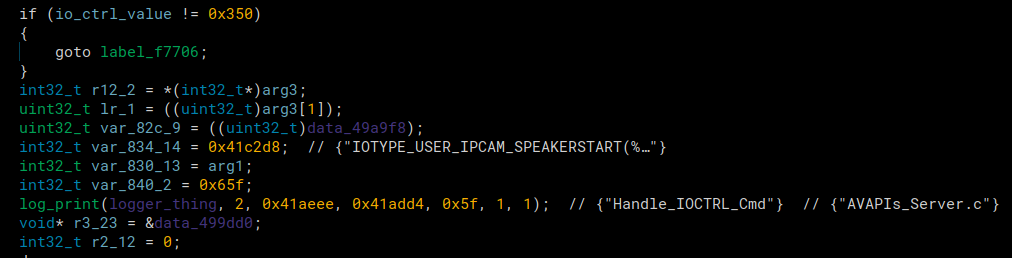

At the log print funtion, we see that it says “Handle_IOCTRL_Cmd” as one of the input strings, this was the 3rd argument. Our script goes through every function call to log print, gets it’s third argument, and renames the function with the log print in it to that third argument. The function that called the log_print in the picture above was renamed to “Handle_IOCTRL_Cmd”.

Binary Ninja Script courtesy of Playoff-Rondo

log_print_sym = bv.get_symbol_by_raw_name("logger")

rename_count = 0

refs = bv.get_code_refs(log_print_sym.address)

for ref in refs:

try:

hlil = ref.function.get_llil_at(ref.address).hlil

label_addr = ref.function.get_parameter_at(ref.address,None,3).value

label_string = bv.get_ascii_string_at(label_addr).value

#print(ref.function.start,ref.function.name,label_string)

ref.function.name=label_string

rename_count+=1

except:

pass

print(f"Finished. Renamed: {rename_count} functions")

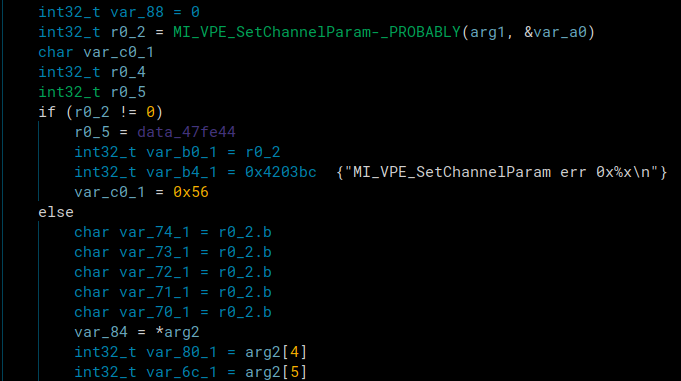

The second renaming script we used was for functions that were called, and then an error was printed if it returned an error code.

An example is in the image above. A function was called and a branch was taken based off the function’s return value. If it wasn’t 0, it printed the name of the function and and error message. We could use that print to rename the function called. It’s renamed already because we had already run the script when the image was taken.

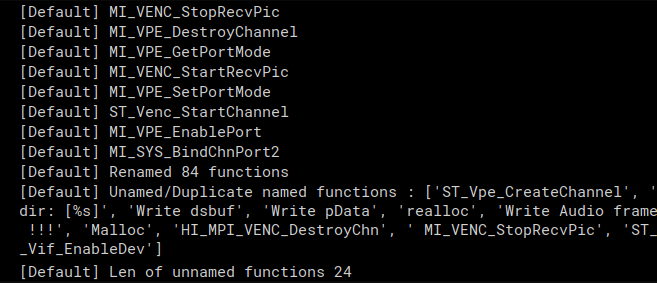

The script below grabs all the error messages that are likely from a failed function call and then checks a few instructions back if there was a function call before it and renames it if there was. This one is much more unreliable and renamed a lot less functions. It would also list the strings that were likely function names but couldn’t find a function call before there error string so they could be manually renamed.

Binary Ninja Script:

Click to expand

count = 0

substrs = ["err 0x", "err:0x", "Fail !", "fail!!", "fail !"]

max_search = 10

extra_characters_in_string = 10

strings = bv.strings

test = "MI_VENC_CreateChn"

# Get all strings and turn to function names

chosen_strings = set()

for astring in strings:

for substr in substrs:

if substr in astring.value:

value = astring.value.split(" err")[0]

if "(" in value:

value = value.split("(")[0]

if " Dev" in value:

value = value.split(" Dev")[0]

if " fail" in value.lower():

value = value.lower().split(" fail")[0]

new = StringReference(bv, 0, astring.start, len(value))

chosen_strings.add(new)

print(f"Number of strings found matching substr {len(chosen_strings)}")

# Get already named function

function_names = list()

functions = bv.functions

for function in functions:

name = function.name

if "sub_" in name:

continue

for string in chosen_strings.copy():

if "_PROBABLY" in name:

name = name.replace("_PROBABLY", "")

print(f"Number of functions that MAY be renamed {len(chosen_strings)}")

count = 0

unnamed_functions = list()

for string in chosen_strings:

refs = bv.get_code_refs(string.start)

found = False

for ref in refs:

offset = 0

instr = "None"

while(True):

try:

instr = str(ref.function.get_llil_at(ref.address+offset).hlil)

except:

pass

offset+=2

if instr != "None" or offset > 2000:

break

lines = bv.get_functions_containing(ref.address)[0].hlil

lines = str(lines).split("\n")

lines = [x.lstrip().rstrip() for x in lines]

if instr in lines:

index = lines.index(str(instr))

for i in range(0,max_search):

try:

check_line = lines[index-i]

except:

break

# Make sure we don't pass an already named function

# And then misname one above it

for name in function_names:

if name in check_line:

found = True

break

# Check for unnamed function in line

if 'sub_' in check_line:

address = re.search('sub_(.*?)\(', check_line)

temp=int(address.group(1),16)

func = bv.get_function_at(temp)

print(string.value)

function_names.append(string.value)

func.name = string.value + "-_PROBABLY"

found = True

count += 1

break

if found == True:

break

if found == False:

found2 = False

for name in function_names:

if "MI_SYS_SetChnOutputPortDepth" in name:

print(name, string)

if string.value not in name:

continue

else:

found2 = True

if found2 == False:

unnamed_functions.append(string.value)

print(f"Renamed {count} functions")

print(f"Unamed/Duplicate named functions : {unnamed_functions}")

print(f"Len of unnamed functions {len(unnamed_functions)}")

Both these scripts combined allowed us to know the name of about 1600 function calls which was very nice to have when reversing.

Packet Reversing

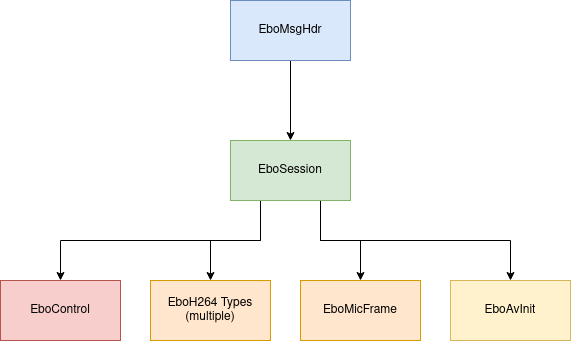

Reversing what these packets were doing was very tedious, but we managed to do it. Every type of packet has its own components which track sequences numbers, branches in the code, tokens, etc. At this point we can debug the target and capture the network traffic in wireshark, but it’s too overwhelming to look at the bytes without dissecting them.

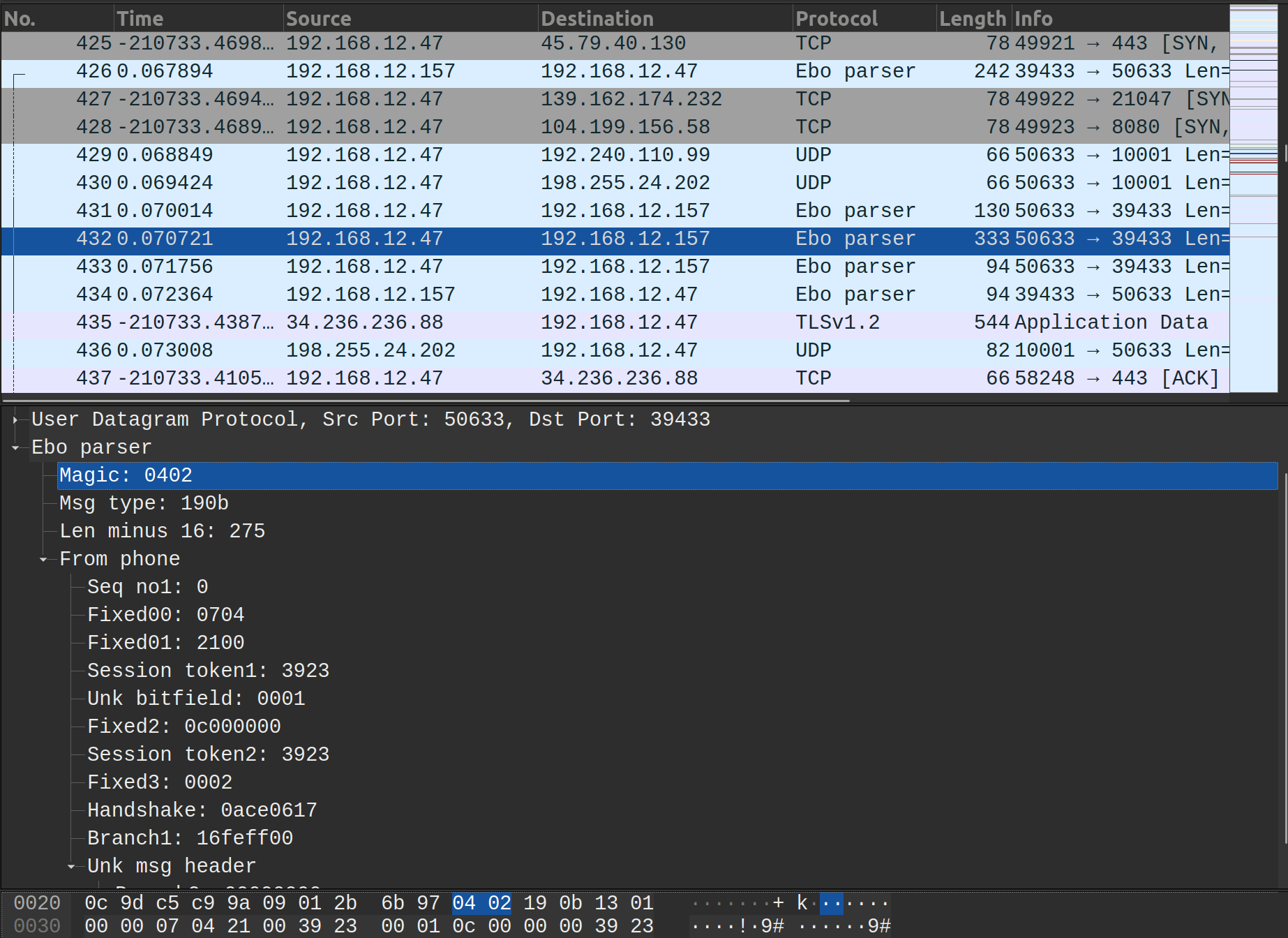

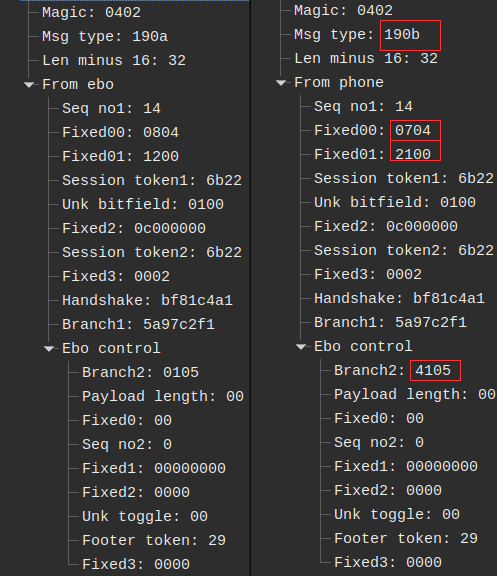

We chose to use the kaitai language to help us after finding this project which can convert a kaitai file to a wireshark dissector! Lain3d’s fork of the project supports conditional statements, which are pretty necessary for this protocol. This allowed us to actually browse the packet capture like this:

It’s super neat that we can just write the specification of the packet structure in kaitai’s simple format and the lua is generated for us.

This is a snippet of the kaitai sequence for the enabot header:

seq:

- id: magic

contents: [0x04, 0x02]

- id: msg_type

size: 2

- id: len_minus_16

type: u2

# if 0xadd8, its a poll to remote server

# checking if accessing not on same wifi

if: msg_type != [0xad, 0xd8]

- id: connection

type: connection

if: msg_type == [0x19, 0x02]

- id: from_ebo

type: control

if: msg_type == [0x19, 0x0a]

- id: from_phone

type: control

if: msg_type == [0x19, 0x0b]

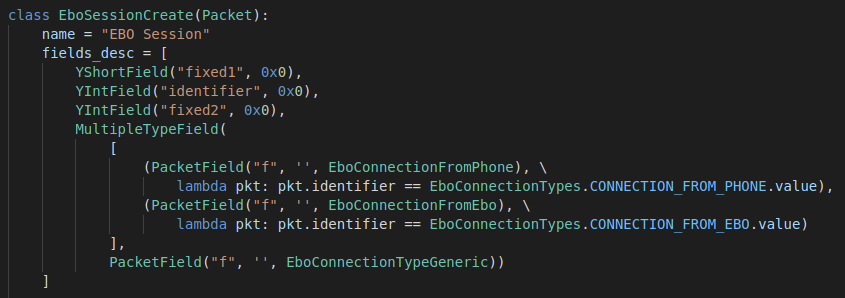

This worked well for deserialization, but what about for reserializing the data, since we want to be able to host our own enabot server? For this task we wrote the definitions for the packet structures using scapy.

Explaining all these packet definitions at once doesn’t seem possible, so the best way is probably to just go through a branch of the ebo protocol and explain each field. Then the important parts of meaningful packets can be explained.

Note: Since we don’t actually know what each branch was when we started reversing. Alot of these types may not have the best names, but they aren’t really worth changing till we’re sure what they are, if that ever happens.

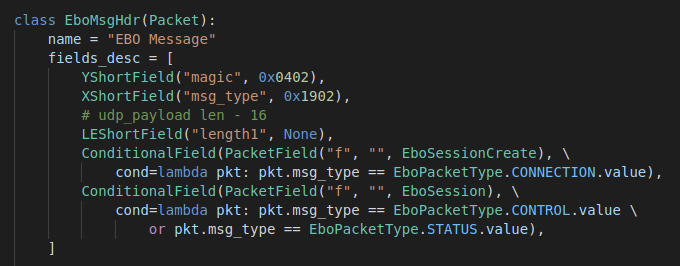

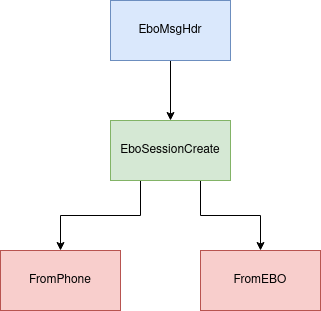

Ebo Message Header Layer

Every packet going to or from the device started with this:

- The first two bytes are always

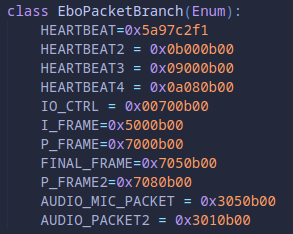

0x0402 - The second two bytes determine whether it’s a connection, control , or status packet. Control packets allow the device it’s communicating with to actually control the state of the device so control packets are sent from the host device. Connection packets are for devices connecting to the ebo. Status packets are sent from the ebo to connected devices to update the status of itself or send data.

- The

ConditionalField’s determine what the next portion of the packet would be compared to the values in theEboPacketTypeenum

- The

- Length1 is the length ebo protocol portion of the packet minus 16

- Example: Motor packets are total length 115, their ebo protocol portion (UDP data portion) is 73. 73 - 16 = 0x39 so the value in the packet would be 0x3900 (little endian)

- Note: Most of the fields are big endian, unless in the scapy definition the field starts with “LE”.

From here, the packet can either use a EboSessionCreate type or an EboSession type:

Ebo Session Layer

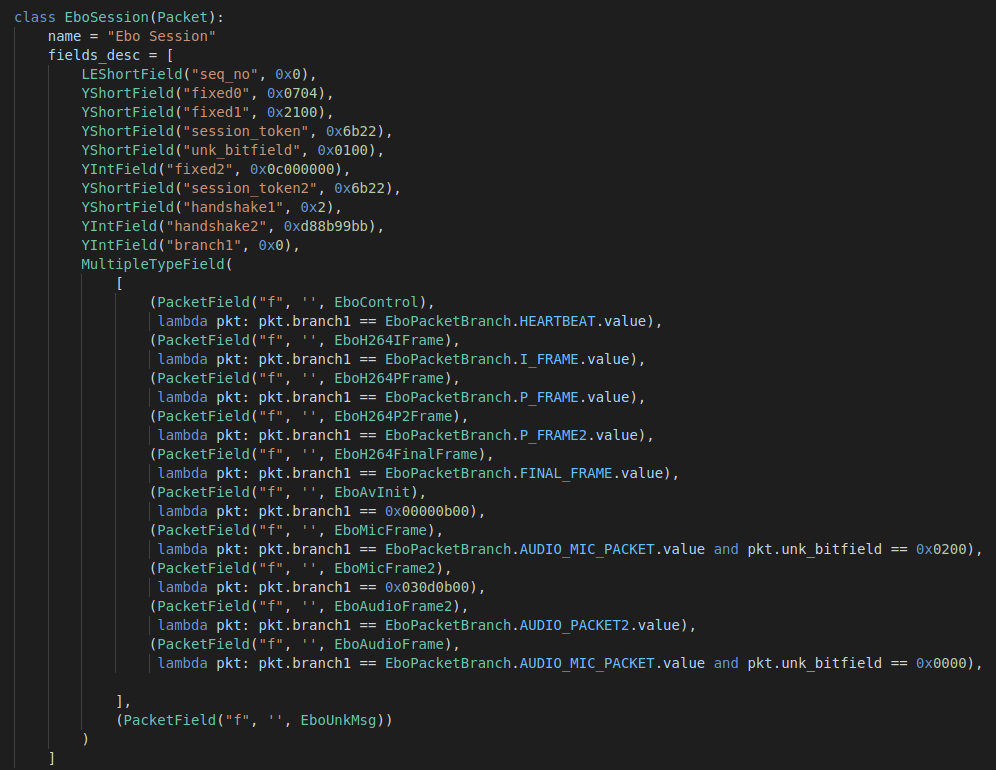

Almost all packets after the original session creation are EboSession packets, regardless of the direction of the packets.

seq_no: The first two bytes are the sequence number of the control packets. As each control packet is sent to the device, this value is incremented by 1.fixed0 + fixed1: The next two values are always fixed as0x07042100session_token: Just a value sent by the host device initially that is included all the packets as some form of validation. After the connection is made the ebo will only accept packets with that same value. We always use the same value when we connect.unk_bitfield: An unknown field that is always either0x0000if sent from the ebo or0x0100if sent from the hostfixed2: Another fixed value that’s always0x0c000000session_token2: Another instance of the agreed upon valuefixed3: Another fixed value of0x0002handshake: This value is similar to thesession_tokenvalue. It’s just an agreed upon value that is sent from the host as validation that the packet originates from the same place after the connection is established. All control packets have to have the correct handshake to be accepted by the ebo after the connection is made.branch1: This is the first big branch in the packet types. It gets split up into different various things

Ebo Session Creation Layer

The FromPhone and FromEBO layers are mostly the same, except the fixed4 is filled data differs in content and in length depending on the direction of the packet. Other than that it is always the same. The fixed data is more complex if it is coming from the phone, but is still unknown.

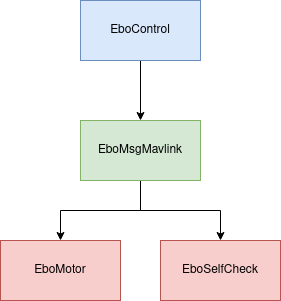

Ebo Control Layer

So far we have observed these packets being used for

- Controlling the motors

- Using skills

- SelfCheck mode

- Heartbeats / Acknowledgements

The EBO is constantly sending what we call “heartbeats” to the phone that are basically messages that terminate after the EboMsgMavlink header with no further payload. They are further discussed in the section on EboServer creation.

More of the Same

That really covers the basics of how these packets are layed out. Every path taken will just have more of the same with random fixed values, branch values, sequence numbers, etc. Now that there is a basic understanding of what these packets are doing, it’ll be easier to explain the packets we actually care about. First we’ll talk about the tooling we developed so that it can be referenced and understood as the packets below are explained. Keep in mind we developed these tools as we went.

Controlling the Ebo

We had reversed a lot of the packet protocol, but we still haven’t covered how we actually sent them to the ebo to control it. The sections below will go over each functionality (that we care about) of the ebo. We’ll go over how we were able to enable the functionality such as motor control, and then how we sent/recieved the packets to actually interact with the ebo.

Motor Packets/Button Packets

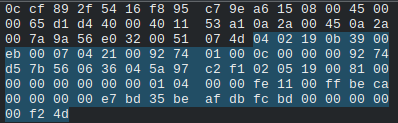

Below are two motor packet which will be referenced in this section for comparison

Some things mentioned in the packet section above should stand out like the sequence numbers increasing, the fixed values, and the token/handshake values. But other than that, how do we know this is a motor packet? The most telling thing is that it’s length 115 (we can see that in wireshark, we don’t expect you to count them). We setup wireshark, and started moving the ebo. When we did that we noticed packets of length 115 came through. When we stopped moving the ebo, they stopped appearing.

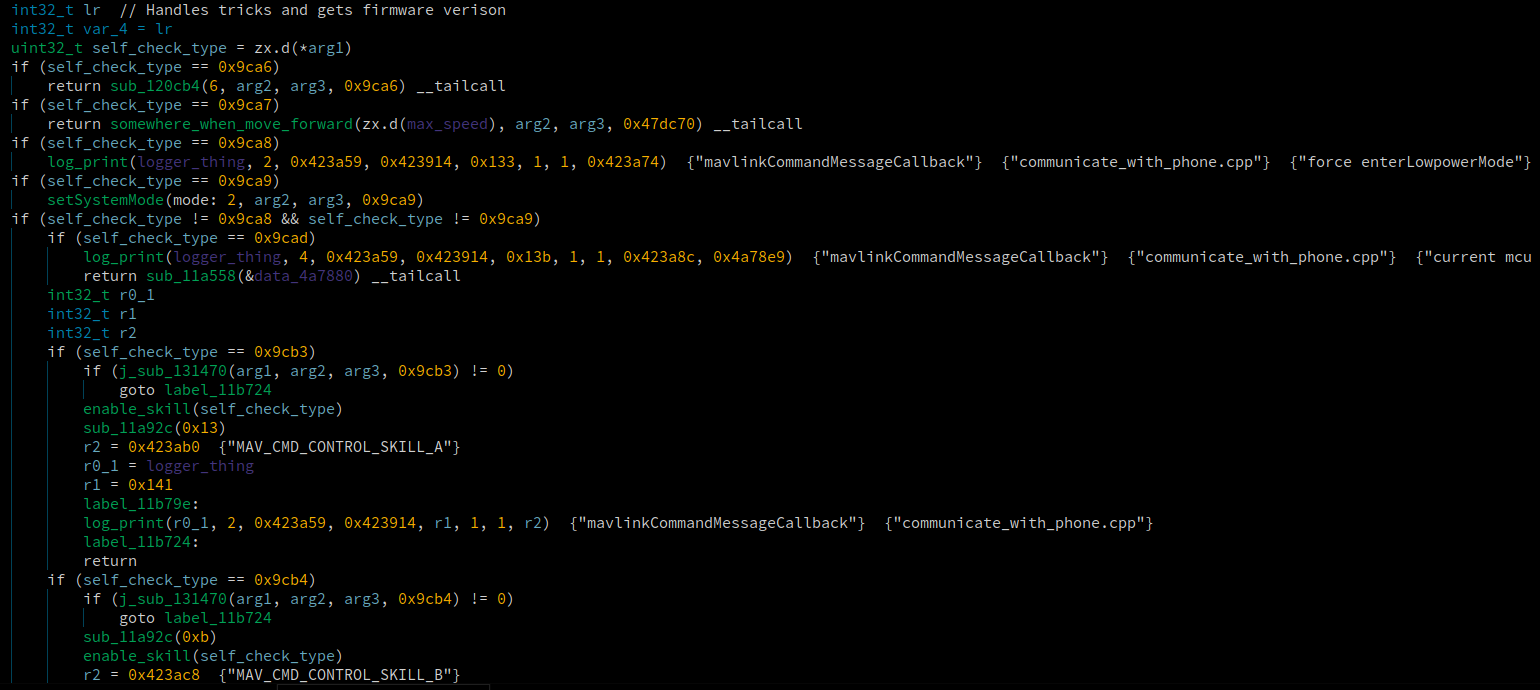

After staring at packets long enough and pressing enough buttons on the app, we could tell that the value 0xbeca (seen in the packet above) was somehow controlling the branch of what buttons we pressed because the 0xca byte would change depending on what button. THEN we noticed that some of the buttons would have ANOTHER branch value immediately after that. Below is a packet of a pressed button, and we’ll go through the decompiled code using the branch values to figure out which button was pressed.

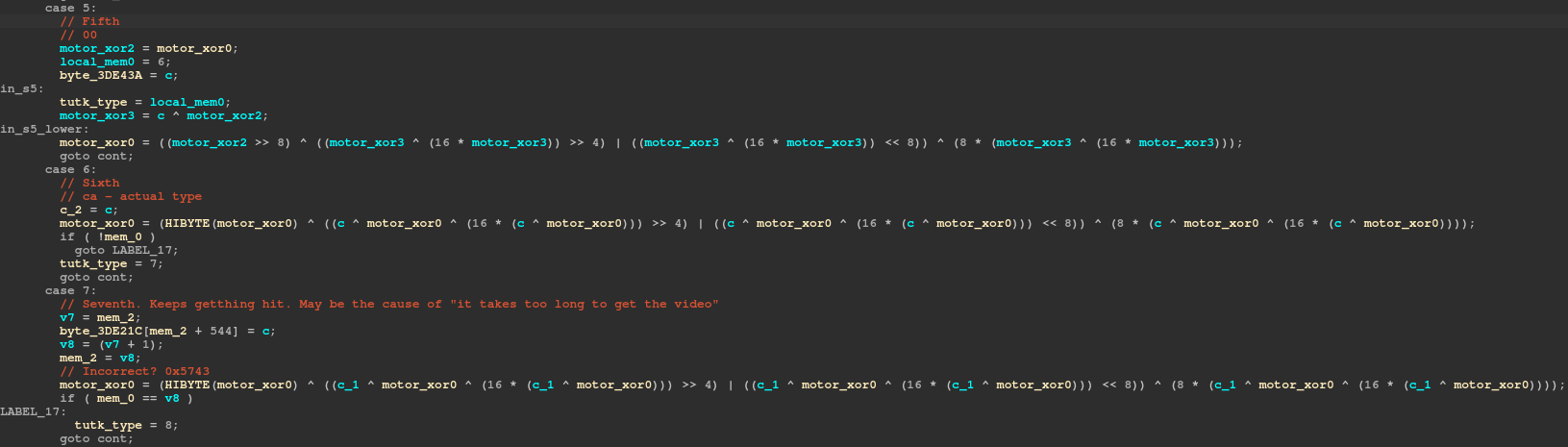

At 0x5e we see the value 0xbec8. Now that 0xbe seems to always be constant, but the 0xc8 changes depending on what we press. We can see some of the branches based off that value below in the decompilation of the firmware.

if (mode??? != 0xd7 && mode??? == 0xc8)

Shows that when that value is 0xc8 we take that branch and we enter the enterSelfCheckingMode function. A little bit further down though we see

if (mode??? == 0x2d)

This is another branch that is taken when you start/stop recording a video because we can see the string that tells us that the camera’s status. When we press the record button in the app we could find a packet with the value 0x2d at that spot and we’d know it’s a packet to start recording.

So let’s enter the enterSelfCheckingMode function, to then see the branches that can be taken inside of there…

Now we see evern more branch values, and if we compare them to the packet above, the 0x9cb3 branch value will stick out. Remember the value is little endian, so even though it’s 0xb39c in the packet, when the code gets it, it interprets it as 0x9cb3. If the value 0x9ca8 it would be a forceEnterLowPowerMode packet based off of the strings.

So based off the string MAV_CMD_CONTROL_SKILL_A we know it was a “skill button”. The ebo has various buttons that make it do random stuff like spin, or shake. This string let’s us know those buttons are referred to as skills and can be easily identified now.

Now that we undestand the branch values of these types of packets, it should be easy to just go into the decompilation and see what the motor packets are doing if we find the right branch where it’s value is 0xca!

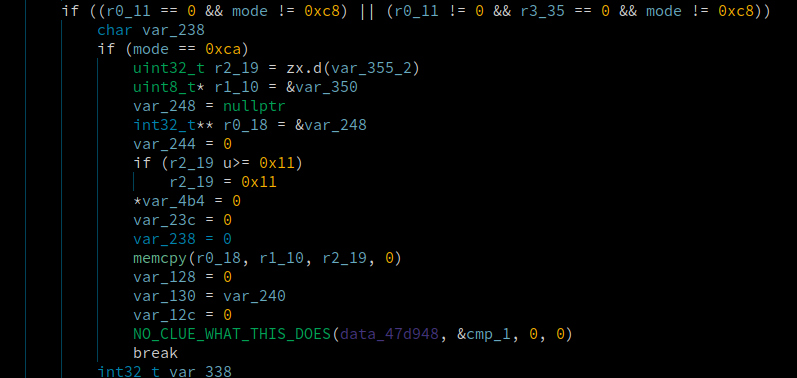

If only. More often then not we’d go to a function which had our branch and we would have no clue what it was doing, and figuring it out would be a lot of work. We know it takes this branch because of the 0xca but the function it goes into seems to just unlock and lock some threads.

This is why we spent some of our time reversing in wireshark. Some of these packets we didn’t even need to look at the decompiled code to figure out what was happening. We could just use trial and error. Especially as we got more and more accustomed to how this protocol worked. However, when we hit a brick wall with this approach, then we would reverse the relevant function, usually with a better picture in mind from the info we learned doing the trial and error.

In this case, trial and error was the way to go. In the two motor packets we see 8 bytes in the last full row of bytes. The packets have different values for these values. We figured that since we knew all other parts of the packet, those values must control the direction and speed. So we setup a test.

A capture was started, then the ebo was only moved forward, the capture was stopped, and a new capture was made only moving backwards, etc. until we had all 4 directions.

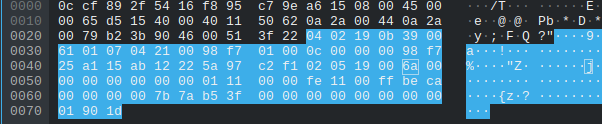

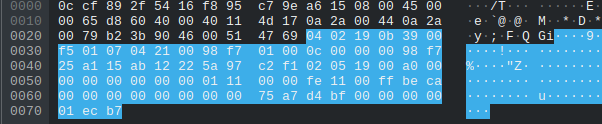

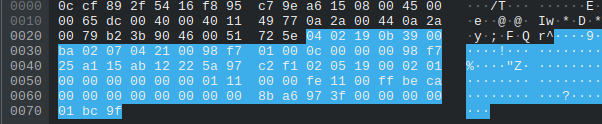

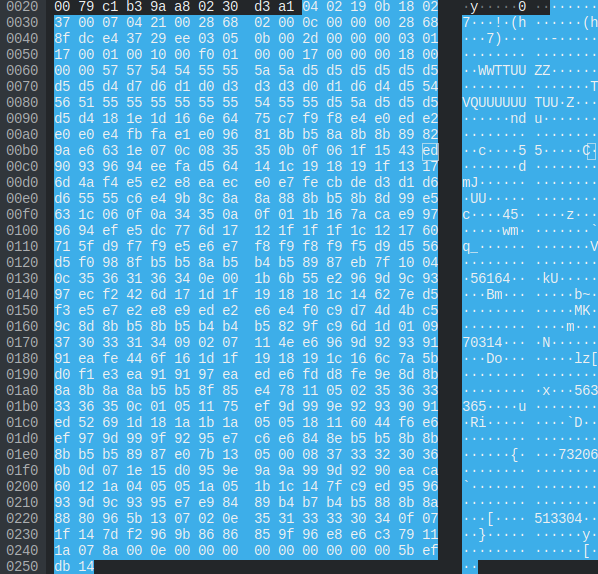

Then we compared the bytes of the packets and after a little testing using the ebo_server motor functionality and adjusting values in the motor packets slightly, it was easy to figure out what was happening. Keep your eyes focused on the lines of hex on offset 0x60 in the following packets and try and spot the patterns.

For awhile thought that on the motors were controlled only by the last byte such as 0xbf or 0x3f since the other bytes would’ve been a massive int value. After looking back at it we realized that each group of 4 bytes is and IEEE float number and 0x3f and 0xbf were just chaning the value to positive or negative. For example the motor value for the “Right” image above is 0x3f97a68b which is really 1.18477 in float32. The value for the “Left” image is 0xbfd4a775 which is really -1.661360 in float32.

Using simple convertsions, we were able to actively add a slider to control the speed of the ebo in the ebo server GUI.

Audio Packets

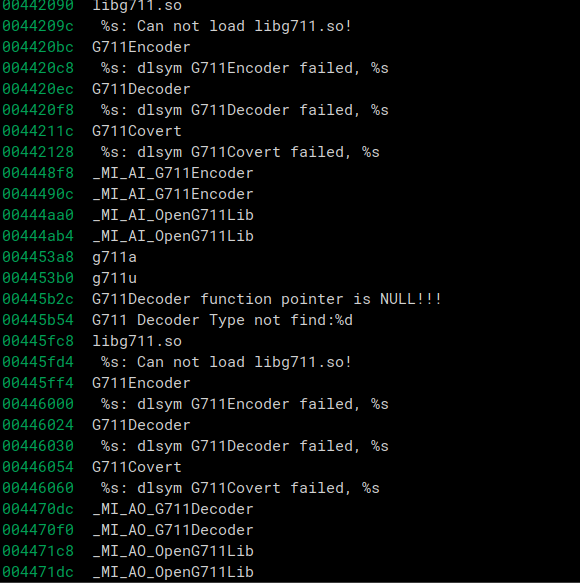

Looking through the firmware and filesystem, we knew that it was encoding the audio in the G711 format just based off of strings and filenames.

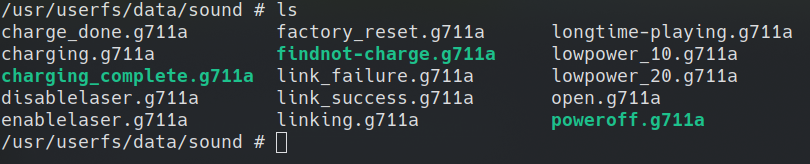

G711 strings in the firmware

Files with the .g711a extensions

This will be covered more in depth in the ebo server section where we dicuss the G711 format and how we were able to send and play audio in realtime on the ebo server.

Video Packets

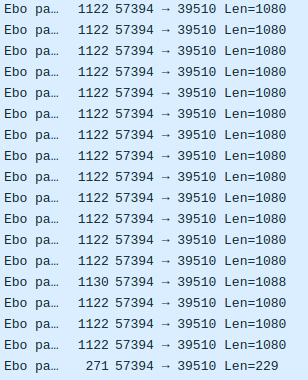

The video packets were very easy to identify in wireshark. Video data is going to be alot larger than any other packet because it’s a bunch of raw data being sent. So all the packets that were length 1122 stood out. Even moreso since all the data after the ebo procol stuff was just a bunch of random bytes. The only thing we didn’t know was what format the data was in. Knowing nothing about video streaming, we just looked at the strings in the firmware. RTP, h265, and h264 all stood out and seemed to have to do with video stuff.

Way too much effort was put into looking at the code and debugging trying to figure out where it encoded the video. The answer was just in the captured packets.

All the video packets came back to back so it was obvious to tell where the frame started, and then at the end there would still be a long packet, but it wouldnt be length 1122, and that was obviously the end of the frame.

The first packet in the sequence always had the value 0x0141 at offset 0x65 (see image below). After a bunch of googling, some forum post talked about those bytes being the start of an h264 P-Frame. More googling and another forum or something talked about using ffmpeg to convert h264 data to a video. So we tried appending all the bytes that we assumed to be video data and ran it through ffmpeg to see if it would pop out a video file. That didn’t work. Then we noticed that some of the sequence of video packets had the header 0x01d7. Some more googling later, it turned out that was the start of a I-Frame.

From the little bit we read about h264 from doing this research it seems that I-Frames are the initial frame of a video and P-Frames then modify that frame until the next I-Frame is sent. Basically, the video has to start with an I-Frame or it won’t have an initial base to modify and thus can’t produce a video. So we wrote a parser to parse all the video packets, and appended their h264 data together while making sure the first frame of the video was a P-Frame. We did this based off of the branch1 values in the packets.

The FINAL_FRAME was the last packet in a frame transmission, so the packet that’s length 271 a few images above would have that branch value. The P_FRAME2 value appeared in packets that were length 1130 but there were some additional fields that made the packet slightly longer. They still had the P-Frame header though, so looking into them further wasn’t worth the time.

Now all that was left was running the parser and generating the video. Apparently the appended bytes don’t need run through ffmpeg and it can just be renamed to .mp4, but it was still done initially anyways. After running it through ffpmeg a real playable video popped out! We could now play video sent from the ebo by capturing, decoding, and stripping the bytes from packets.

Hosting an EBO Server

Initial Server

For the standalone server, we basically want to see how far we can get pretending to be the phone. At first we tried simply replaying the packets the phone sent, while also fixing up obvious stuff like the ip address in the connection request so that the Ebo communicates with our PC instead of our phone.

The session looks like it starts successfully, but the actual things done during the session like movement, skills, etc, do not work. We think this is due to the session token changing each time as well as the sequence numbers of packets coming from the ebo drifting away from the ones we are sending as acknowledgement packets in the replay.

With this in mind we decided to go ahead and try to implement our own simple server/client. We say server/client because it kind of behaves as both. Our server sends a connection to a fixed port of a server hosted on the EBO. But instead of responding from the same port, the response comes from a random source port that is used for the remainder of the session. This is to facillitate multiple users connecting at once.

Starting the session is fairly simple, we can mostly replay the connection packets from the beginning of the session to start a new session to our pc. One issue we had was the EBO disconnecting about 20 seconds after the session started.

From looking at the normal session in wireshark we noticed a few changes that happen in the response the phone sends back to the EBO upon receiving a packet.

When we take these into account and resend the message then it will stay connected.

Trying to send motor packets

Above we described the structure of the motor packets. We thought we understood the packet structures fairly well but we had a fair bit of trouble getting the EBO to actually move on demand from sending these packets via the server once connected. The EBO would only move once when we sent a duplicated packet from a past capture! It would not move again upon sending the same packet, most likely due to the sequence number being the same. If we changed the sequence number in order to increment it, the EBO still wouldn’t move! We played with the fields and no matter which field we changed, the EBO would no longer move. This was frustrating as it felt like we were vere so close.

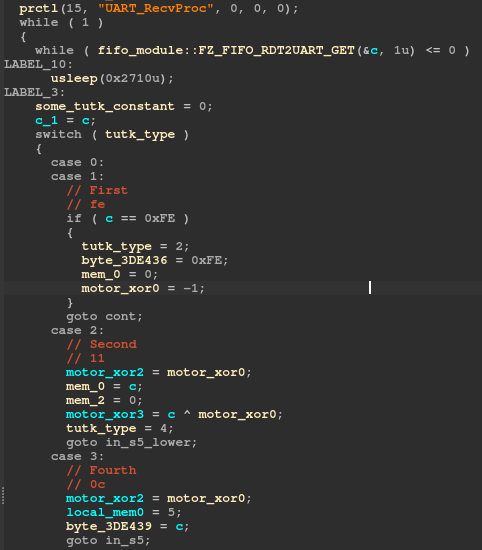

To solve this we needed to spend time understanding the layout of the different subsystems running on the EBO. The strategy was simple, we needed to find a spot that breaks for the “good” motor packet, but not for a “bad” motor packet, where something has been changed. Once we have this, we can follow the logic backwards until we find why it’s not making it through. However, there are a lot of threads running from the FW_EBO_C process. UART_RecvProc is the active thread upon decoding a received packet.

Memory breakpoints were incredibly useful for finding where another thread interacted with the data seen written in one thread when it seems we have come to a dead end. Using this method we were able to determine the UART_RecvProc thread, which is responsible for reading RDT messages from the packet receive thread in a pub-sub like manner.

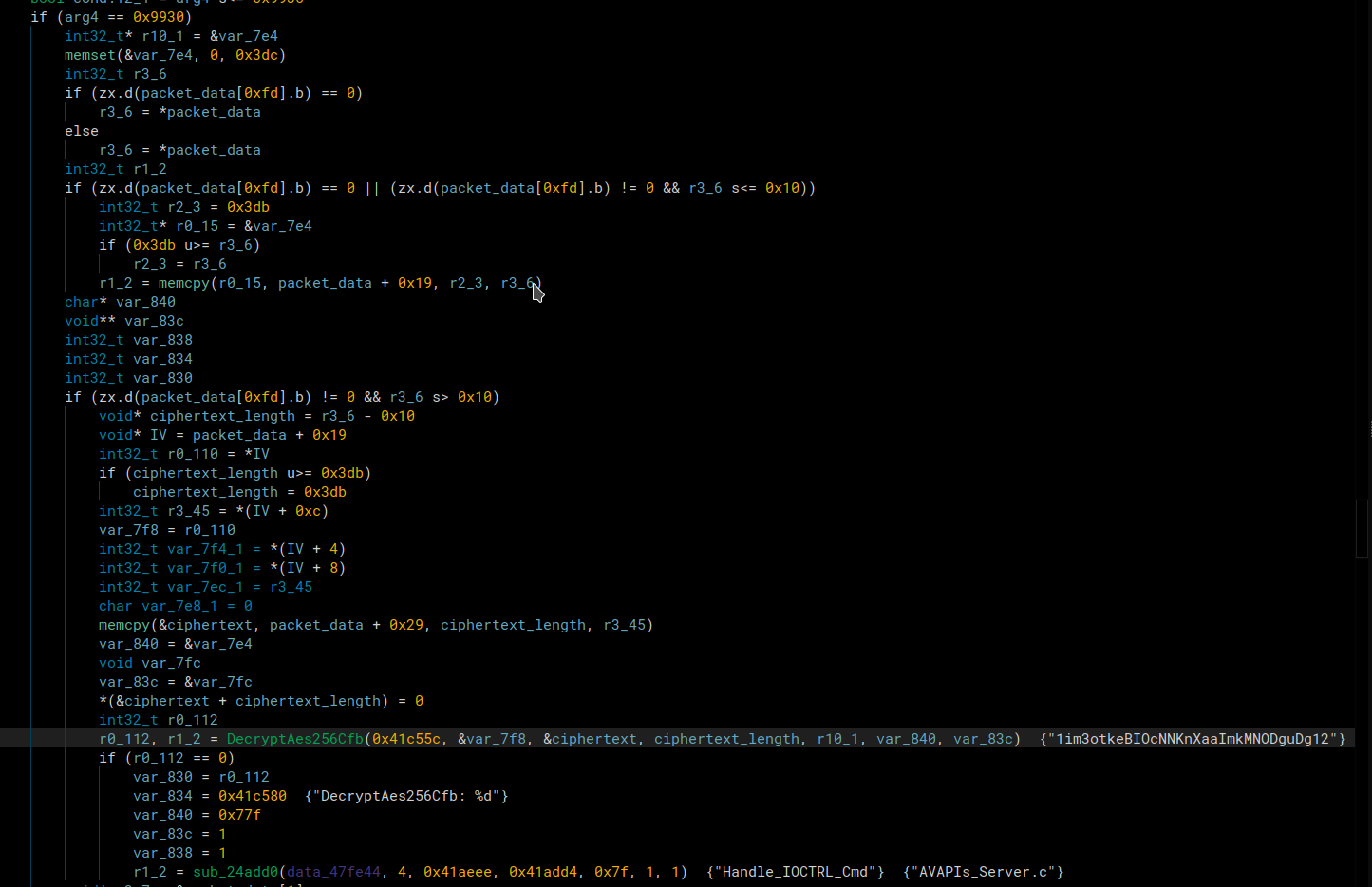

The receive part of the thread acts as a state machine. One byte of data comes in at a time. It starts at stage 0, and then depending on the byte that comes in, the state changes accordingly.

We can read out the entire “message” that is sent to this thread and compare it to the corresponding step in the state machine:

EboMsgMavlinkType Action motor1 motor2 crc

v v v v v

data: [fe 11] 00 0c 00 [ca] 00 00 00 00 00 00 [40 be 00 00] [00 00 00 00] 00 00 01 [15 27]

stage: [01 02] 04 03 05 [06] 07 07 07 07 07 07 [07 07 07 07] [07 07 07 07] 07 07 07 [08 09]

The expected crc is calculated based on this message and some global data that is constant. We opted to reimplement the algorithm and call it from our python code to get the expected crc.

u8 cmds[] = {0xc4,0x2c,0xd3,0x22,0xe8,0x2a,0x13,0xde,0x56,0x44,0x64,0x41,0xdf,0x75,0x79,0x9e,0x72,0x4d,0x54,0xe2,0x09,0x20,0xb6,0x4e,0xed,0x97,0x64,0x9f,0xa4,0xd0,0x34,0xd9};

u32 calc_crc(u8* buf) {

u32 tutk_type = 1;

u8 mem_0;

u8 mem_1;

u8 mem_2;

u8 mem_3;

u32 local_mem0;

u16 motor_xor0;

u16 motor_xor1;

u32 motor_xor2;

u8 motor_xor3;

u8 c_2 = 0;

u32 v4;

u32 v5;

while(1) {

u8 c = *buf;

buf = buf+1;

switch(tutk_type) {

case 0:

case 1:

if (c == 0xfe) {

tutk_type = 2;

// missing assignment

mem_0 = 0;

motor_xor0 = 0xffff;

}

goto cont;

case 2:

motor_xor2 = motor_xor0;

mem_0 = c;

mem_2 = 0;

motor_xor3 = c ^ motor_xor0;

tutk_type = 4;

goto in_s5_lower;

case 3:

motor_xor2 = motor_xor0;

local_mem0 = 5;

// missing assignment

goto in_s5;

case 4:

motor_xor2 = motor_xor0;

local_mem0 = 3;

mem_3 = c;

goto in_s5;

case 5:

motor_xor2 = motor_xor0;

local_mem0 = 6;

in_s5:

tutk_type = local_mem0;

motor_xor3 = c ^ motor_xor2;

in_s5_lower:

motor_xor0 = ((motor_xor2 >> 8) ^ ((u8)(motor_xor3 ^ (16 * motor_xor3)) >> 4) | ((u8)(motor_xor3 ^ (16 * motor_xor3)) << 8)) ^ (8 * (u8)(motor_xor3 ^ (16 * motor_xor3)));

goto cont;

case 6:

c_2 = c;

motor_xor1 = c;

motor_xor0 = (HIBYTE(motor_xor0) ^ ((u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))) >> 4) | ((u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))) << 8)) ^ (8 * (u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))));

if (!mem_0) {

goto s7_lower;

}

tutk_type = 7;

goto cont;

case 7:;

unsigned char v7 = mem_2;

u32 v8 = (u8)(v7+1);

mem_2 = v8;

motor_xor0 = (HIBYTE(motor_xor0) ^ ((u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))) >> 4) | ((u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))) << 8)) ^ (8 * (u8)(c ^ motor_xor0 ^ (16 * (c ^ motor_xor0))));

if ( (u8)mem_0 == v8 ) {

s7_lower:

tutk_type = 8;

}

goto cont;

case 8:

v4 = (u8)(motor_xor0 ^ cmds[c_2-0xc8] ^ (16 * (motor_xor0 ^ cmds[c_2-0xc8])));

v5 = (HIBYTE(motor_xor0) ^ (v4 >> 4) | (v4 << 8)) ^ (8 * v4);

v5 = bswap_16(v5);

//printf("crc: : %x\n", v5);

return v5;

}

cont:

mem_1 = 0;

continue;

}

}

Once we added this step to our scapy extension, we could move the EBO as desired!

Starting the AVServer

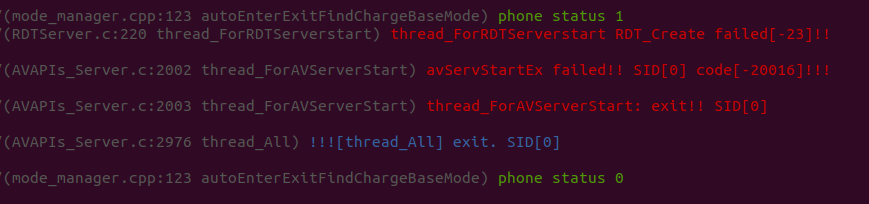

Our next goal was to get the AVServer up so we could get some audio/video packets.

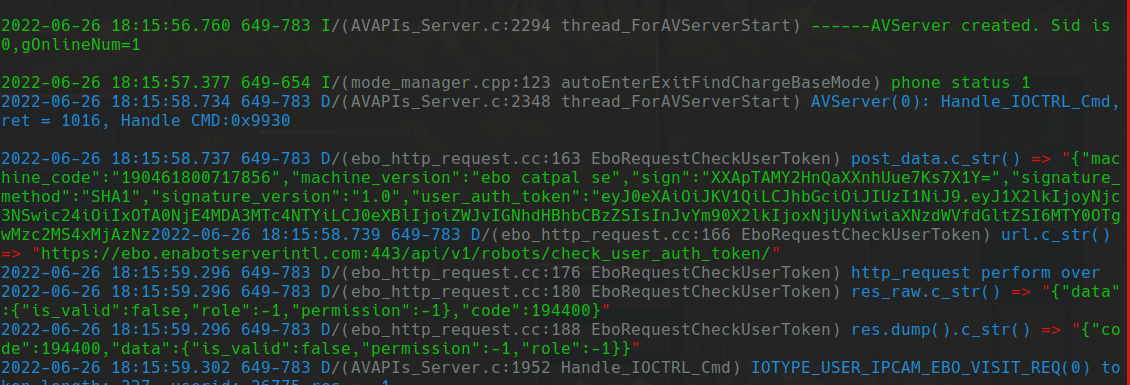

The log prints after restarting FW_EBO_C were very useful for this whole process. We could compare the messages one at a time to see which appeared when we sent what packet.

2022-05-30 01:48:20.692 650-650 I/(AVAPIs_Server.c:3834 FZ_TUTK_Init) ------New connection created. Sid is 1,Cnt=2 gOnlineNum=1

2022-05-30 01:48:20.696 650-753 D/(AVAPIs_Server.c:2173 thread_ForAVServerStart) SID[1], thread_ForAVServerStart, OK

2022-05-30 01:48:20.751 650-753 D/(AVAPIs_Server.c:2238 thread_ForAVServerStart) Client(1) is from[IP:10.42.0.68, Port:55935] Mode[LAN] VPG[41496:1:41] VER[3030201] NAT[2] AES[0] gucMode[0]

The messages above would appear when we connected from the phone, but when we connected from the ebo server, we didn’t see that 3rd message. Looking in wireshark we could see that the next non heartbeat packet sent after our last one was a length 640 packet.

The bytes inside of this packet had some kind of ID string. And then a 32 byte value later down in the packet. After looking around the filesystem we found the matching string in /configs/token. The file had the matching ID string followed by another string. Our intuition led us to believe the 32 byte value in the packet was a SHA256 and that it was of the string that followed the ID. We were correct! The SHA256 matched of the string matched the 32 byte value found in the packet.

Manually crafting that packet with the values from the token file and sending it to the ebo allowed that 3rd log message to appear that we weren’t seeing before. We were one step closer to getting video packets!

Starting the video packets

After starting the AVServer, we still weren’t seeing any video packets.

When we connected from the phone we saw that it would make a request to it’s API server to validate a sent token. It was obvious the packet length 1118 was triggering this because it was close after the 640 and was the only packet long enough to hold an encoded JSON token.

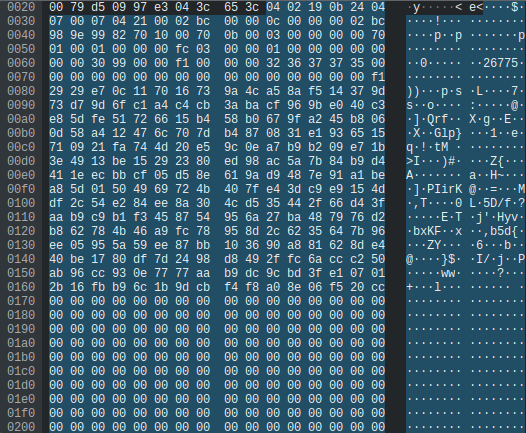

Looking at the branch value of the packet (0x9930), we were able to track it down in the decompilation.

Through some dynamic analysis before the call to AES_decrypt, we were able to match that part of the packet was the IV, the key was hardcoded in the firmware, and the rest of the packet was the ciphertext. After decrypting it, we got that json string as seen in the image above.

This means we know the key, and control the iv, and ciphertext, so we can completely encrypt and send our own requests. As long as we can create a valid key for their check_user_auth_token API, we could connect with our own custom key. This is something we still have to test though, so for now we’re just copying a fresh 1118 length packet and sending it. If it’s recent enough and hasn’t expired, we get all the matching log messages that let us know we’re one step closer to getting video packets from the our ebo server.

In the packet snapshot above, we can see the IV and ciphertext as 2 of the fields we parsed in our wireshark dissector

If we send a length 1118 packet from an old pcap with a key that has expired, we get these log messages

Notice the final green line where it has “false” and “-1”’s. This lets us know if our key has actually worked or not. Even though we were sending an expired key that returned -1, we were still able to move onto the next step of starting the camera, with or without the API’s permission.

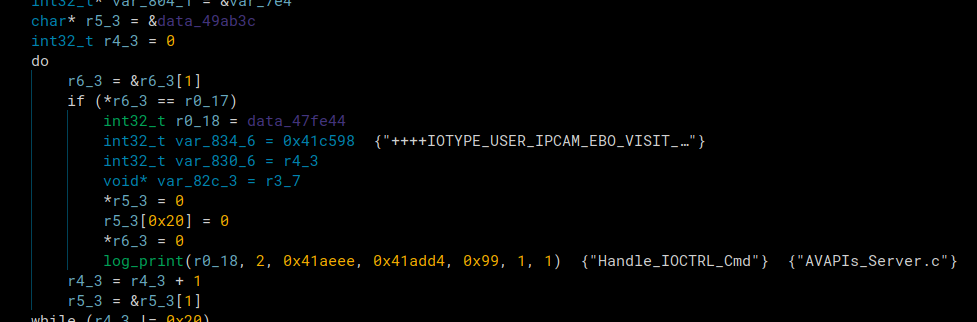

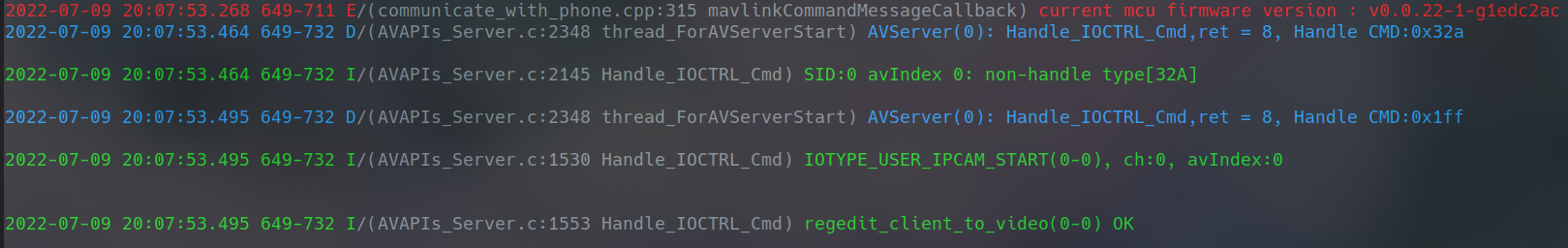

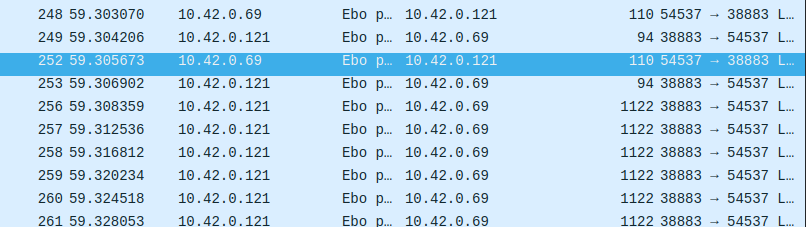

There were 2 final packets we knew we had to send because they would show up as ‘Handle_IOCTRL_Cmd’s in the logs. We could also see where this was getting hit in the decompilation.

They both have hex command values, so we looked at wireshark and were easily able to identify which packets were triggering these log messages. They were the packets that were length 110.

Notice bytes 0x63-0x62 are 0x32a. There is another packet almost identical to this one but it has 0x1ff as the two bytes, and then immediately after the video packets start appearing in the capture.

Initially even though we knew we had to send these packets, when we did it wasn’t working. After messing around with sending some of the packets that preceeded them, the video packets started rolling in! With some additional testing it came with a catch. If we connected to the to the ebo from a phone, every time we connected to the ebo from our ebo server, it wanted heartbeat messages from the app. When it didn’t get them, it disconnected from our ebo server. We get around this by just restarting FW_EBO_C after connecting from a phone.

We were then able to implement the video packets recieved into our ebo server and made a full GUI with the video stream.

Starting Speaker and Mic packets

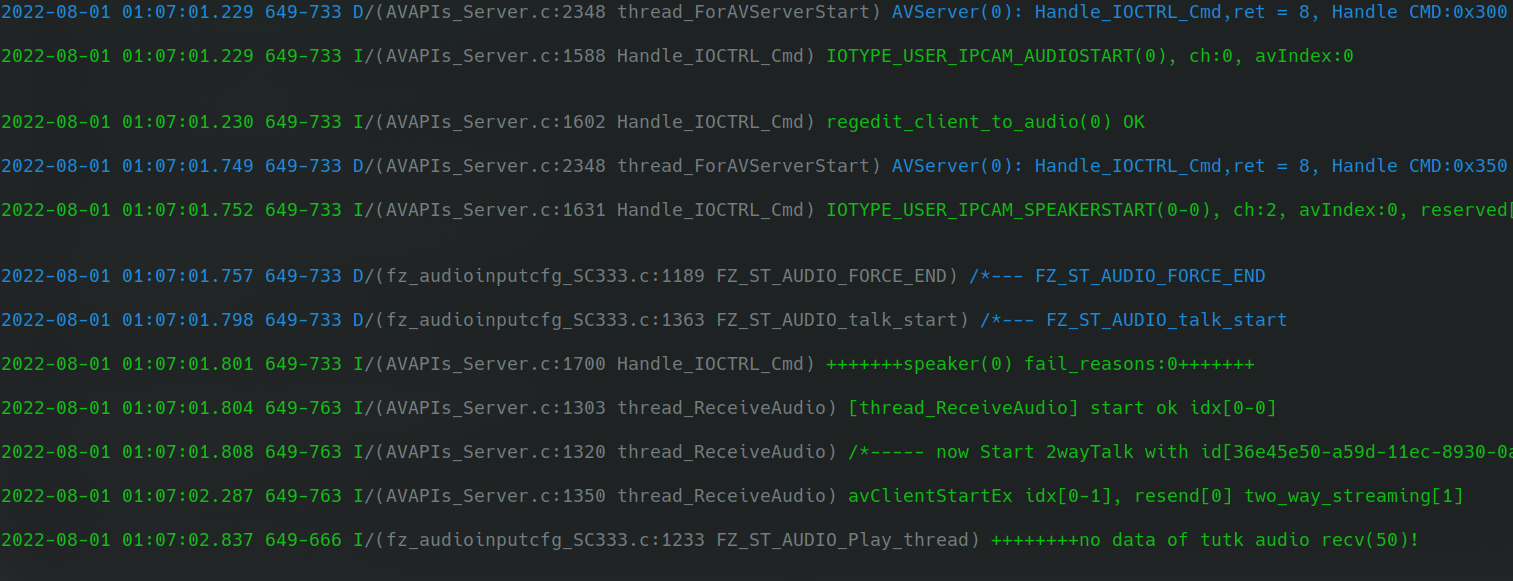

After starting the video, we also had trouble starting the microphone and speaker data. We knew what packets we had to send because they were the same 110 length “Handle_IOCTRL_Cmd” packets that we had to send to enable the video. However when we sent them, they weren’t enabling. Again after some trial and error of sending more packets, we figured out we had to send a few packets before AND after the IO_CTRL_Cmd packets this time. Once we did that the audio data started rolling in and we knew we could send microphone packets to it.

Code where it branches to enable the audio

Code where it branches to enable the microphone packets

Log of us enabling audio and microphone. When both the speaker and microphone are enabled, it enables “2wayTalk”. The final message “no data of tutk audio recv(50)” is printed when the microhphone is enabled but no microphone packets are being received.

Speaker Packets

We could tell that the packets coming from the Ebo that were length 370 were the speaker packets because they only showed up when we enabled the speaker in the app.

After looking through the firmware we could tell it was encoded with the G711 audio codec based on the strings. We also realized that the audio files ended with “.g711a” in the configs folder.

If we concatenated all the bytes together from a packets capture from wireshark, we could run it through FFMPEG and hear what we said through the phone.

ffmpeg -f alaw -ar 8000 -i test.g711a output.wav

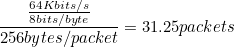

The bandwidth of G711 is supposed to be 64Kbits/s and this lined up with what we saw. Every second, about 32 audio packets would come through. Each audio packet contained 0x100 bytes.

This just verifies that what we were seeing makes sense.

We want to playback the audio live as it comes through using pyaudio.

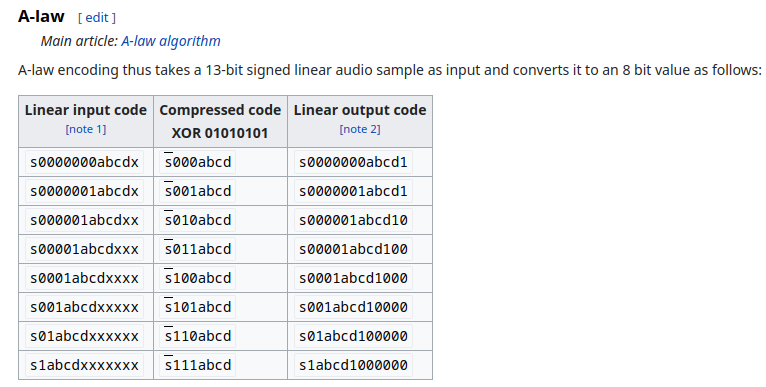

Keep in mind G711 is a lossless compression algorithm that reduces size of data being sent by 50%. So when we decode the a_law data it doubles in size, but the sample rate remains the same even though each sample decoded sample is 2 bytes instead of 1.

Since each byte in G711 is a sample and there are 256 samples per packet we can set out block size to 256, and our frequency is 8000. After decoding the data using the decode_alaw function from the G711 package, we can write the bytes to our pyaudio stream and hear the audio perfectly through our speakers.

Mic Packets

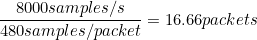

The mic packets were the same as the audio packets, but with a slightly modified samples/second. There were 0x1e0 bytes of data in each packet instead of 0x100.

Since more data is being sent in each packets, we know that the samples per packet was different. We can do

Looking through wireshark it was safe to say that about 16-17 packets were sent every second for microphone data so this again lined up.

Since we semi-verified the frequency is again 8000Hz we know it’s probably G711A again. Therefore we know that the samples per packet is 0x1e0 since again each byte is 1 sample.

Now we can grab microphone sound from our microphone using pyaudio. We set the frequency to 8000 and the block size to 480 (0x1e0). Then we read data from our pyaudio microphone steams in chunks of 480 and send it to the ebo server to then send to the ebo. After implementing all this, we could hear ourselves talk through the ebo.

Unfortunately there is a loud whitenoise in the background, but we added mute buttons for both the audio and the microphone in the GUI so that it doesn’t get annoying after awhile.

Ebo Server In Action

Conclusion

This post covered a lot of information about reversing the ebo’s protocol. We started all the way back from getting a shell on the device and ended up being able to craft a custom server to connect to the ebo and have full control over it’s audio, microphone, motors, and camera.

The next step is finding a vulnerability that will let us connect to the ebo from our server without knowing the ID numbers or token beforehand. This could be accomplished by finding a vulnerability in the packet parser that we could develop and exploit for to get a shell on the device or have it send back a packet containing those things. Then we could simply read out of the token file and be able to connect.

Next post we hope to cover the following.

- Emulation of the packet receive function with Qiling so that we can fuzz the packet input

- We have already begun working on this. We can emulate and fuzz from the packet receive function, but have to fix issues with the emulation such as it trying to access threads that don’t exist.

- Identifying a vulnerablity from one of the crashes that could possibly be exploited

- Developing an exploit that will let us control memory and get a shell

- Using memory/shell access to manipulate the Ebo so that it will accept a connection from the ebo server without a proper key or ID number.

Tools

- Decompilers / Static Analysis

- Languages

- Python3

- C

- Bash

- Debuggers / Dynamic Analysis

- Packet analysis